Russia’s oil exports came under renewed scrutiny in early February after U.S. President Donald Trump said Washington had agreed a trade deal with India that would cut tariffs on Indian goods from 50% to 18% in exchange, besides other concessions, to an end to Russian crude imports. The prospect of losing one of Moscow’s largest post-2022 buyers triggered Russian concerns over export revenues and budget stability. Yet available trade data points in the opposite direction.

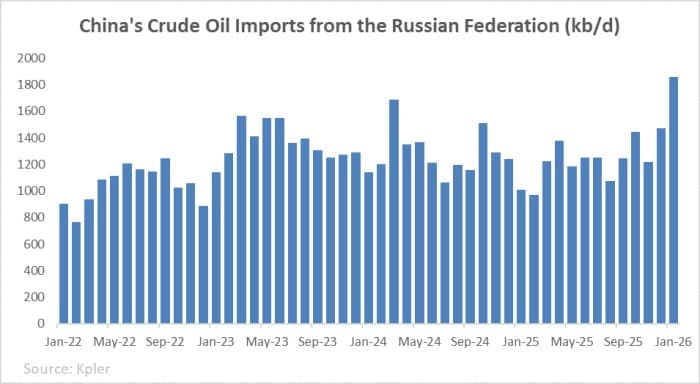

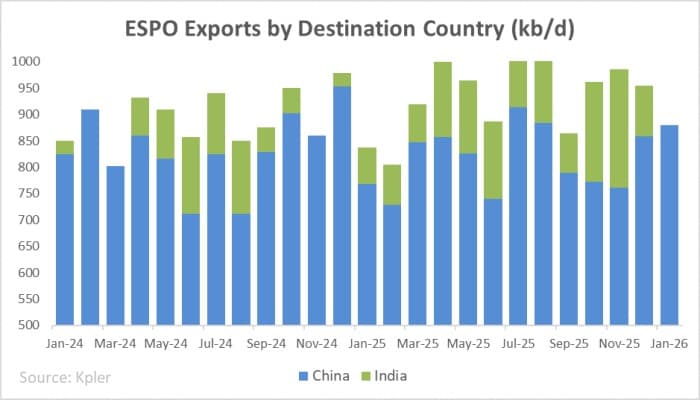

The numbers are clear: for Russia, hope now speaks Chinese. January 2026 marked the strongest month on record for Sino-Russian oil trade, with seaborne exports reaching 1.86 million b/d, building on an already record-high January 2025. More than 50% of volumes were loaded at Kozmino, near Vladivostok, and at Sakhalin. For the first time since November 2024, 100% of Russia’s ESPO exports were directed to China. Even excluding pipeline supplies of around 820,000 b/d, Russia’s seaborne shipments alone were 46% higher than Saudi Arabia’s exports, with Riyadh shipping just 1.2 million b/d in January despite its long-standing position as Beijing’s leading seaborne supplier.

Pricing remains the first and most obvious driver. Market analysts tend to overstate the scale of Russian discounts, which for Urals, following weaker Indian demand, now appear closer to $7 per barrel versus ICE Brent. That margin alone is sufficient to attract Chinese refiners toward Russian barrels, especially when Moscow absorbs much of the logistical, insurance, and security burden – a familiar feature of Russia’s post-sanctions trading model. In effect, Russia has internalized much of the geopolitical risk, allowing Chinese buyers to focus primarily on price and supply stability.

Strategic considerations reinforce this commercial logic. Washington’s increasingly confrontational foreign policy has limited the number of Beijing’s reliable suppliers. Venezuelan exports to China averaged 500,000–600,000 b/d in 2025 but remain politically fragile. Iranian shipments to China, which averaged at about 1.2 million b/d in 2024 and the first half of 2025, have been declining since June 2025, following strikes on Iranian nuclear facilities and a increasingly stringent US sanctions on Tehran’s oil trading ecosystem. For Beijing, these disruptions have underscored how quickly politically exposed supply chains can unravel. Eventually, Russian crude (discounted, geographically proximate, and not susceptible to politically driven disruptions) has become one of the few large-scale sources that combines volume with predictability. Moreover, Kozmino, the largest terminal for Russian crude exports to China, is just 5-6 shipping days from major Chinese ports, making it not only one of the safest but also the closest large-scale sources of crude for the Chinese market.

Infrastructure developments have further locked in this union. The new Shandong Yulong refinery, with capacity of 400,000 b/d, has emerged as a structurally Russian-oriented buyer. Sanctions imposed by the EU and UK in mid-2025, followed by US measures targeting Rosneft and Lukoil, effectively closed the refinery off from most Western and Middle Eastern supply channels. With few alternatives, Yulong has turned almost entirely to Russian crude. Apart from two Canadian cargoes before the sanctions took effect, the refinery has relied exclusively on Russian oil since October 2025. In December and January, it imported an average of 240,000 b/d from Russia, and two Aframax tankers loaded with ESPO have already discharged there in February 2026.

The growing interconnection between Beijing and Moscow is also reshaping India’s political and trade vision. A prolonged deepening of Chinese-Russian energy ties would intensify concerns in New Delhi about being left out of one of Asia’s most strategically important commodity corridors. For India, oil imports are turning into not a commercial matter but rather a geopolitical instrument. Watching Russia pick China as its dominant Asian outlet may ultimately push India back toward Russian barrels, regardless of political pressure from Washington – driven not only by price incentives, but by the desire to avoid strategic sidelining from a long-standing partner.

If that dynamic holds, the Trump administration’s attempt to use trade leverage to curb Russian energy revenues may prove counterproductive. Instead of isolating Moscow, it is accelerating the formation of a more potent Eurasian energy alliance, anchored by China’s demand and Russia’s supply. India, rather than exiting this system, may eventually be drawn back into it. Three years after Western sanctions were meant to sever Russia from global markets, Moscow is exporting more crude to its largest customer than ever. Ultimately, the main beneficiary is Washington’s principal strategic rival. China is securing larger volumes of crude at increasingly competitive prices without assuming significant new risks. For now, the record flows through Kozmino and else suggest that pressure from Washington is reshaping trade routes – but not breaking them.